The Western saddle traces its genesis to

Spanish and Mexican influences. These saddles initially came in

to use on cattle ranches and grazing lands where the cowhorse

worked cattle for the vaquero. As cattle ranching spread from

Mexico north, three separate styles of Western saddles evolved.

Geography and the type of cattle influenced this emergence of

different styles of saddle. These working cowhorses and working

cowboys needed tack that made their jobs safer and easier. The Western saddle traces its genesis to

Spanish and Mexican influences. These saddles initially came in

to use on cattle ranches and grazing lands where the cowhorse

worked cattle for the vaquero. As cattle ranching spread from

Mexico north, three separate styles of Western saddles evolved.

Geography and the type of cattle influenced this emergence of

different styles of saddle. These working cowhorses and working

cowboys needed tack that made their jobs safer and easier.

In open areas such as parts of

California, the cowboys worked the cattle by roping them. The

wide-open spaces allowed the cowhorse to line the cowboy up with

a running cow so he could throw a lariat to rope it. The cow

was then dallied to the saddle by the lariat. The dally was

loose so that the horse would not be jerked off its feet or its

withers jarred by the saddle as the running calf hit the end of

the rope.

In the Texas brush country,

however, the cowhorse was trained to move the calf out of the

brush by cutting it out of the herd and brush so that the

wrangler could get a good throw. Since the calf was not

generally running, this cowboy roped and tied the calf tight to

the horn. In the Texas brush country,

however, the cowhorse was trained to move the calf out of the

brush by cutting it out of the herd and brush so that the

wrangler could get a good throw. Since the calf was not

generally running, this cowboy roped and tied the calf tight to

the horn.

Besides stout horns for

dallying the ropes with several hundred pounds of calf at the

other end, the Western saddles were developed with the back

cinch. This second cinch kept the saddle in place when the calf

hit the end of the rope and when the cowhorse worked the calf by

taking up the slack as the wrangler dismounted to rope the

calf.

While the Western saddle has a

rich New World Spanish history, it is still evolving today. At

one time, the Western saddle served the cowboy in making his

living. It had to be stout, dependable and designed for the

comfort of the horse and the safety of the rider. Today, the

Western saddles are still ridden for cow working, but a whole

new pleasure industry is demanding a different kind of Western

saddle. Today we will find basically three types of Western

saddles.

The

Western equitation saddle is designed

for showing or parades. The saddle

is built almost to force the rider into the correct equitation

seat. It is heavily tooled, ornamented with silver

and generally designed to look pretty. While it should

meet the criteria for fit for both rider and horse, it is not a

working saddle and was not designed to hold up to the rigors of

ranch work. A dallied calf would simply rip the horn right

of this type of saddle. The seat is heavily padded and

built up in the front to throw the rider into position.

Swells are medium height.

The

Western Roping Saddle, on the other

hand, is made to stand up to the rigors of

ranch work. It is heavy duty and stout weighing

considerably more than the

equitation saddles. The horn is

designed to hold a roped calf - at least 3 inches in diameter

and 3 inches high. The swells and cantle of the roping

saddle are low and designed not to interfere with the cowboy's

dismount. equitation saddles. The horn is

designed to hold a roped calf - at least 3 inches in diameter

and 3 inches high. The swells and cantle of the roping

saddle are low and designed not to interfere with the cowboy's

dismount.

The All Purpose Western

Saddle

is light weight, deep

seated with high swells and cantle to keep the rider secure and

comfortable. Most have a padded seat for long hours on the

trail. The horn is much smaller and less sturdy since the most

that is dallied around it is a canteen or horn bag.

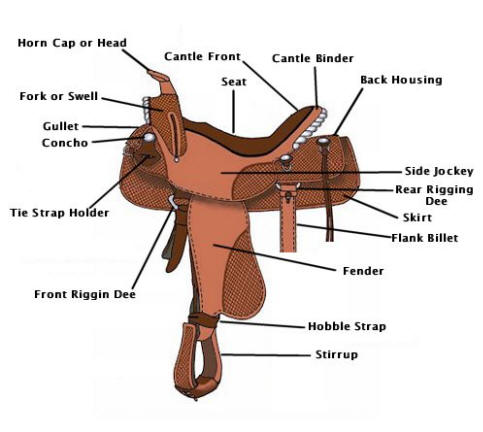

Parts of the Western Saddle

The foundation on which any

saddle is built is the saddle tree. For the western saddle,

traditionally the tree was made from beechwood covered in

rawhide. Given the new materials available, modern trees may be

made from anything from wood to pressed laminated wood to fiber

glass. There are standard trees or you can have one custom made

to fit your mule. The foundation on which any

saddle is built is the saddle tree. For the western saddle,

traditionally the tree was made from beechwood covered in

rawhide. Given the new materials available, modern trees may be

made from anything from wood to pressed laminated wood to fiber

glass. There are standard trees or you can have one custom made

to fit your mule.

If made of wood, the newer

saddles have trees made of plied wood. Plied wood is layered

with the grain placed facing in different directions and glued

under high pressure. This process creates a tree that is warp

resistant and superior in strength to solid wood. The tree is

made up of the fork, the horn, the bars and the cantle.

The gullet and the swells make

up the fork. The gullet is that part which gives shape to the

fork and extends across the withers. The height and width of

the gullet is determined by the width of the mule and the

intended use of the saddle. In most western standard made

saddles the gullet may range from an average of 5 ¾ inches to 6

¼ inches wide and 6 ¾ inches to 8 inches high. If measured from

swell to swell, gullets average 10

2 to 14

inches.

The swell is the shape the

fork takes from the horn down - modified swell fork to undercut

swell fork. The undercut swell fork resembles a pair of horns

on either side of the saddle horn. This allows the rider to

hook a thigh under the swell to maintain stability during a

quick turn. This undercut style is not preferred by ropers who

might catch a rope on it.

Saddle horns come in a variety

of sizes and materials. Wood, brass, steel or iron can be

covered in smooth leather or rawhide. Horns are attached to the

tree by either bolts or screws and come in types such as

regular, egg-shaped pelican, two rope, high dally or double

dally. Saddle use determines the size, shape and height of the

horn to be put on a saddle. If it's

a roping saddle, the horn will be stout, wide. If it's

a pleasure saddle, the horn will be small in case the rider

needs to grab it for security.

The bars are the part of the

tree that comes in contact with the mule's

back. This is the part that must fit correctly for the optimum

comfort of the mule and correct balance for the rider.

The standard bars include the 5

2 inch Regular, the 6 inch

Semi Quarter Horse, the 6

2 Quarter Horse, the 6 ¾

inch Arab/Morgan. Any other measurement must be custom made.

The cantle rises in the back of the tree and is designed to

keep the rider deep in the saddle. Cantles have different

shapes depending on the work the saddle is designed for.

The configuration of the tree's

parts give the saddle the end silhouette and the best blueprint

for success in the job for which it is intended.

Seats range from flat to built

up, from slick to suede, from small to large. Seat type is the

deciding factor for the comfort of the rider. Each rider will

have his or her preference for the work done in the saddle.

The shape of the seat and the rise from the cantle to the fork

is critical in keeping the rider in the correct position.

Cutters and reiners prefer flat seats that allow the rider more

movement forward and back. Pleasure and trail riders might

prefer a seat that rises steeply from cantle to fork to hold the

rider securely in the seat. This type of seat is also preferred

by the equitation rider because it keeps the rider locked in the

correct position.

Seat measurement is determined by

measuring the distance between the center of the fork across to

the center of the cantle. The rider wants a seat big enough to

allow freedom of movement. It is important that the rider

remain free to move the stirrup leathers freely. Seat sizes

range from 14 ¾ to 15 ¾ inches. When sizing the seat to the

rider, remember to take into account amount of padding, quilting

and rise. All these factors shorten the length of the seat of

the saddle. Remember too short a seat is less comfortable than

too long a seat.

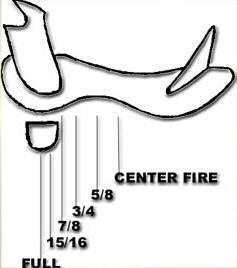

Western Saddle Rigging Western Saddle Rigging

The rigging of a saddle indicates how it is

balanced on the mule's

back and how the girth is attached. As a result of the cattle work

early cowboys had to do, they developed what is called the double

rigging. Double rigging differed from the center fire rigging used

in the English saddles, the old Mexican saddles and the vaquero

saddles, in that it consisted of two rings - one at either end of

the tree.

This double rigging, also referred to

as full rigging or rim rigging, provided greater stability to the

saddle and rider as the cowboy roped, stopped and held a couple of

hundred pounds of moving calf. Greater stability meant less trauma

to the horse's

back from the impact of the calf hitting the end of the rope and

jerking the saddle forward. The double rigging is

now the norm in most Western saddles. This double rigging, also referred to

as full rigging or rim rigging, provided greater stability to the

saddle and rider as the cowboy roped, stopped and held a couple of

hundred pounds of moving calf. Greater stability meant less trauma

to the horse's

back from the impact of the calf hitting the end of the rope and

jerking the saddle forward. The double rigging is

now the norm in most Western saddles.

The other types of rigging may be

found in specialty saddles and antique saddles. For today's

pleasure riders who do not rope, the double rigging may seem

cumbersome. It can prove to be uncomfortable for both rider and

mule. The forward cinch has a tendency to rub the mule directly

behind the elbow when the mule or horse is steep shouldered.  They

are showing interest in a seven-eighths rigging which positions the

front D ring behind the normal position, but still forward of the

center fire point. They

are showing interest in a seven-eighths rigging which positions the

front D ring behind the normal position, but still forward of the

center fire point.

The in-skirt rigging has become

popular with pleasure riders. This rigging has the rings sewn into

the saddle skirting. This type of rigging has minimal bulk under

the rider's

legs, lies closer to the mule and allows the stirrup leathers to

swing more freely. Of course, this type of rigging is not intended

for holding a cow, but is very popular with trail riders, pleasure

riders and those who show their mules.

Some Western saddles come with a

three way rigging which allows the rider to adjust the rigging as

needed. This type of rigging has two slots in it which allows the

rider to choose which slot through which to put the tie strap.

This type of rigging allows for

the many diversities of mules, riders and riding styles. The saddle

purists would quibble with this type of rigging. However, it is

helpful when a rider has a number of mules and does not want to

purchase a saddle with specific rigging for each.

Fitting the Western Saddle

There a two ways to fit the Western saddle to

your mule. One is to have a custom made tree designed for your mule

and the other is to carefully fit the ready made saddle to your

mule. In both cases, the tree is responsible for the comfort of

your mule.

The tree's

bars run along the spine of the mule and spread the weight of the

rider evenly across the mule's

back. The distance between the bars, their flare and their length

affects this weight distribution over the bars.

Regular Bars have a 5

2 inch wide

gullet. They are shaped at a steep angle giving them a narrow

spread. These tend to fit Thoroughbred type mules better.

Semi Quarter Bars have about the

same spread but the gullet is carved out to 6 inches to make the

bars flatter.

The Quarter Horse bars are 6

2 to 6 ¾

inches wide inside the gullet. This bar opens up a bit more to

accommodate the muscular shoulders of the heavier stock mule.

Arabian or Full Quarter Horse bars

are 6 ¾ to 7 inches with flatter angles. This fits the flatter

withered mule better.

In addition, there are saddle

makers who make specialty trees designed for the needs of certain

breeds. Arabian saddles are built for shorter backed animals.

Mules out of Arab and Morgan mares might benefit from this type of

tree.

In order for the fit to be good,

the bars must lay smoothly along the mule's

back. This effectively distributes the rider's

weight evenly along the spine of the mule. Once you cinch up the

saddle, stand two fingers between the mule's

withers and the top of the gullet. If there is not room for your

fingers, the gullet is too wide. If it is too wide, when the rider

puts weight in the saddle and the mule moves, the saddle will hit

the mule on the withers.

The mule's

shoulder must be able to move freely under the bars. To test this

area, slip a hand under the bars of the saddle and have a friend

lead the mule forward slowly. If your fingers get pinched, so will

your mule's

shoulders because

the tree is too narrow.

The bars extend slightly beyond

the point where the cantle is attached to the tree. This provides

support over the mule's

loins and kidneys by distributing the rider's

weight evenly over this tender area of the back. If the saddle

rocks more than an inch from back to front, the bars are not making

good contact and the tree may be too short or too long for the mule's

back.

Keep in mind that a saddle that

fits your mule when he's

two years old may not fit him at six. Saddle fit will be affected

by maturation, weight loss, weight gain and fitness. Even your

custom made saddle may no longer fit as your mule's

back changes as he grows older or becomes more fit. Constantly,

check the fit of your saddle.

In addition, mules inherit

conformation characteristics from both sire and dam. Their back

conformation can be as varied as the breeds of donkeys and horses

used to breed for mules. No two horses are alike. No two mules are

alike.

Fitting the saddle correctly to a

mule's back

is important, not only for the comfort of the mule, but also for the

execution of the maneuver of the job the mule is asked to do. An

ill fitting saddle can be tolerated by most mules. However, if you

want the best for your mule's

comfort and the best performance from your mule, you must have a

correctly fitting saddle. After all, you can't

do your best two step in a tight pair of boots!

|